Class 11 Physics Chapter 8 Mechanical Properties of Solids is an important chapter for CBSE exams and competitive exams. In this chapter, students learn about elasticity, stress, strain, Hooke’s Law, elastic moduli (Young’s modulus, Bulk modulus and Shear modulus), Poisson’s ratio, stress–strain curve and elastic potential energy.

These notes explain every concept in simple language, with proper mathematical derivations, exam-oriented formulas, and step-by-step numericals. The content is fully based on the latest NCERT syllabus and follows the CBSE marking scheme, making it ideal for board exam preparation.

Table of Contents

Introduction

In daily life, solids like iron rods, rubber bands, bridges, and buildings experience forces. The mechanical properties of solids explain how solids deform (change shape or size) and return to original shape when forces are applied and removed.

This chapter helps us understand:

- Why bridges don’t bend easily

- Why rubber stretches more than steel

- Why glass breaks suddenly

Deforming Force

A force which produces a change in configuration of the object on applying it, is called a deforming force.

Elasticity

Elasticity is the property of a material by which it regains its original shape and size after the removal of the deforming force.

Elastic Limit

Elastic limit is the upper limit of deforming force upto which, if deforming force is removed, the body regains its original form completely and beyond which if deforming force is increased the body loses its property of elasticity and get permanently deformed.

Perfectly Elastic Bodies

Those bodies which regain its original configuration immediately and completely after the removal of deforming force are called perfectly elastic bodies.

e.g., quartz and phosphor bronze etc.

Perfectly Plastic Bodies

Those bodies which does not regain its original configuration at all on the removal of deforming force are called perfectly plastic bodies.

e.g., putty, paraffin, wax etc.

Stress

The internal restoring force acting per unit area of a deformed body is called stress.

Its unit is N/m2 or Pascal and dimensional formula is [ML-12T-2].

Stress is a tensor quantity.

Types of Stress

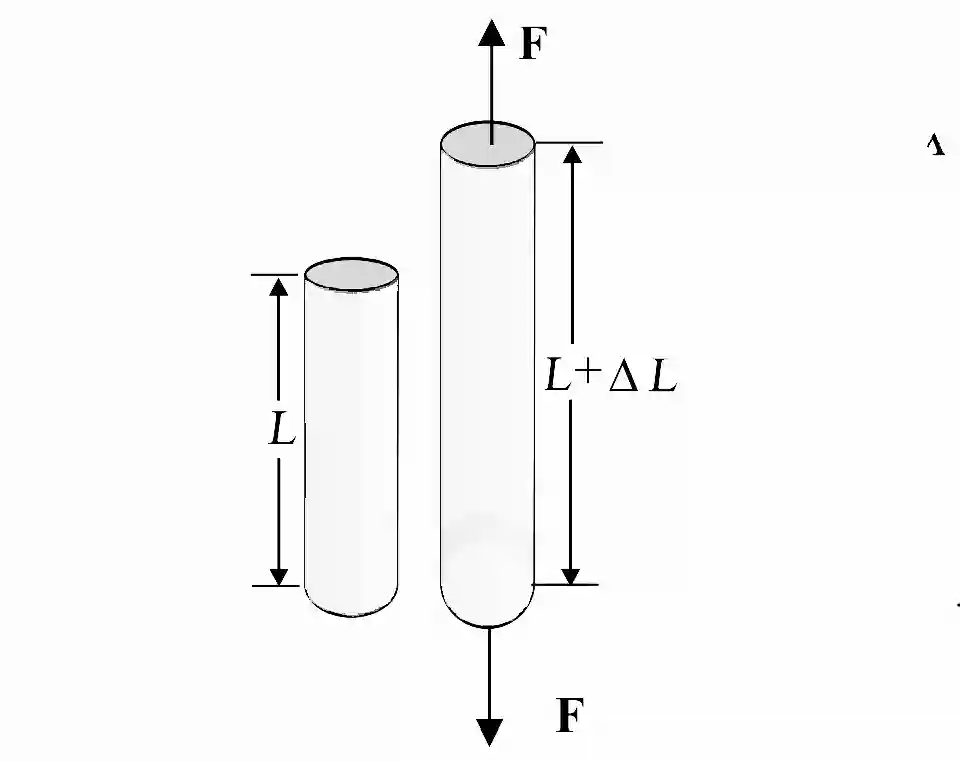

(a) Longitudinal Stress

When the external force acts along the length of a body (perpendicular to the cross-sectional area), the stress produced is called longitudinal stress.

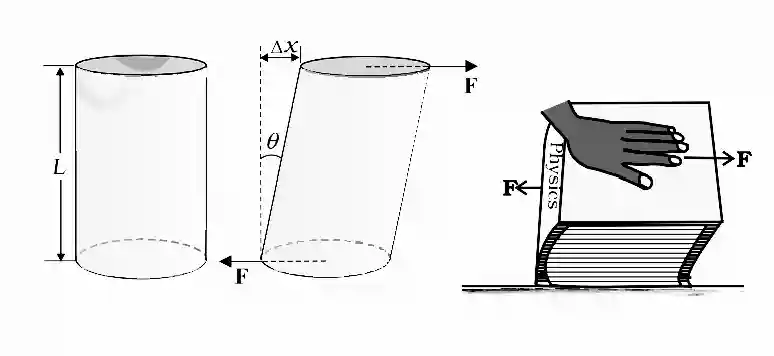

(b) Shear Stress

When the external force acts parallel to the surface of a body, producing a change in shape without change in volume, the stress produced is called shear stress.

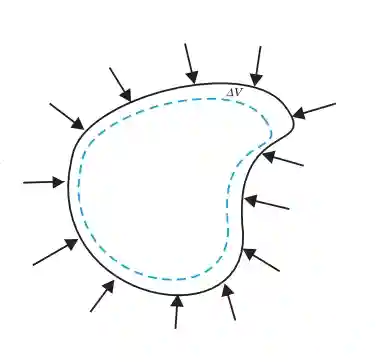

(c) Volume Stress

When a body is subjected to equal and opposite forces from all directions, causing a change in volume, the stress produced is called volume stress.

Strain

When an external force is applied to a solid body, it may cause a change in its length, shape, or volume.

The measure of this deformation is called strain.

👉 Strain is defined as the ratio of change in dimension to the original dimension of the body.

- Strain is a dimensionless quantity

- Strain has no unit

- Strain depends on the deformation, not directly on force

- Strain is produced only when stress is applied

Types of Strain

(a) Longitudinal Strain

When a force is applied along the length of a wire or rod, its length changes.

This change produces longitudinal strain.

(b) Shear Strain

When a force acts parallel to the surface of a body, the body changes its shape without changing its volume. This deformation produces shear strain.

Where:

x= lateral displacementL= height of the bodyθ= shear strain (in radians)

(c) Volume Strain

When a body is subjected to uniform pressure from all sides, its volume changes.

This change produces volume strain.

Example:

- A cube compressed uniformly

- Liquids under pressure

Where:

ΔV= change in volumeV= original volume

Hooke’s Law

Hooke’s Law states that within the elastic limit, the stress produced in a body is directly proportional to the strain produced in it.

Substituting Stress and Strain Expressions

Rearranging the above equation:

Within elastic limit, Stress is directly proportional to Strain

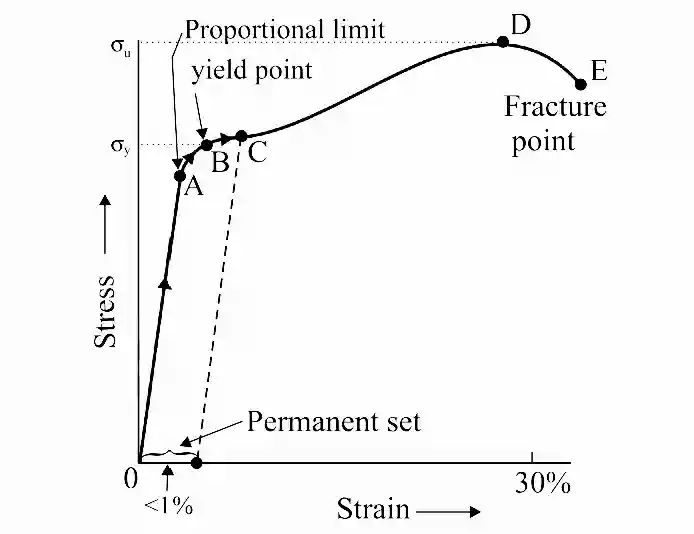

Stress–Strain Curve

A stress–strain curve is a graph plotted between stress (on Y-axis) and strain (on X-axis) for a material when it is subjected to an increasing deforming force.

👉 It helps us understand the elastic behaviour, strength, and breaking point of a material.

| Point / Region | Name | What Happens at This Point / Region | Nature of Deformation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Elastic limit | Up to this point, stress is directly proportional to strain (linear region). On removing load, the material returns to original shape. | Completely elastic |

| B | Yield point | Material begins to yield; large strain is produced with little increase in stress. | Beginning of plastic deformation |

| C | Plastic region (strain hardening starts) | Material has crossed yield point; permanent deformation occurs. | Plastic |

| D | Ultimate tensile stress (UTS) | Stress is maximum; necking just begins. | Plastic (maximum stress) |

| E | Breaking (fracture) point | Material breaks into two pieces. | Failure |

Important Points on the Curve

- O–A : Linear Elastic Region region (Hooke’s Law valid)

- Stress is directly proportional to strain

- The graph is a straight line

- Hooke’s Law is valid

- Deformation is completely elastic

- A : Elastic limit

- Up to this point, the material returns to original shape after unloading

- Beyond this point, permanent deformation begins

- A–B : Yielding Region

- A small increase in stress causes large increase in strain

- Material begins to flow plastically

- B : Yield point

- B–C : Plastic Region

- Material undergoes permanent deformation

- Hooke’s Law is not valid

- C : Breaking point

- The material breaks or fractures

- Stress at this point is called breaking stress

- CD : Plastic Region

- CD represents the plastic region where strain hardening occurs.

- D : Ultimate Tensile Stress

- Maximum stress the material can withstand.

- Beyond D, material cannot sustain increasing load.

- DE : Necking Region

- A neck (thin region) forms in the wire.

- Actual cross-section decreases rapidly.

- Nominal stress decreases even as strain increases.

- PE : Breaking (Fracture) Point

- Point E is the fracture point where the material finally breaks.

Elastic Limit

Maximum stress up to which material behaves elastically.

Yield Stress

Stress at which plastic deformation begins.

Breaking Stress

Maximum stress a material can withstand before fracture.

Elastic Moduli

Elastic moduli are physical quantities that measure the elastic behaviour of a material. They tell us how much a material resists deformation when an external force is applied.

In general,

The ratio of stress and strain, called modulus of elasticity,

Types of Elastic Moduli

5.1 Young’s Modulus (Y)

Young’s modulus is the ratio of longitudinal stress to longitudinal strain.

It measures the elasticity of solids in length.

Example 8.1 A structural steel rod has a radius of 10 mm and a length of 1.0 m. A 100 kN force stretches it along its length. Calculate (a) stress, (b) elongation, and (c) strain on the rod. Young’s modulus, of structural steel is 2.0 × 1011 N m-2 .

Example 8.2 A copper wire of length 2.2 m and a steel wire of length 1.6 m, both of diameter 3.0 mm, are connected end to end. When stretched by a load, the net elongation is found to be 0.70 mm. Obtain the load applied.

Example 8.3 In a human pyramid in a circus, the entire weight of the balanced group is supported by the legs of a performer who is lying on his back (as shown in the following figure). The combined mass of all the persons performing the act, and the tables, plaques etc. involved is 280 kg. The mass of the performer lying on his back at the bottom of the pyramid is 60 kg. Each thighbone (femur) of this performer has a length of 50 cm and an effective radius of 2.0 cm. Determine the amount by which each thighbone gets compressed under the extra load.

5.2 Shear Modulus (G/η)

Shear modulus is the ratio of shear stress to shear strain.

It measures the elasticity against change in shape.

Example 8.4 A square lead slab of side 50 cm and thickness 10 cm is subject to a shearing force (on its narrow face) of 9.0 ×104 N. The lower edge is riveted to the floor. How much will the upper edge be displaced?

5.3 Bulk Modulus (B/K)

Bulk modulus is the ratio of volume stress to volume strain.

It measures the elasticity of solids and liquids in volume.

Negative sign shows decrease in volume

Example 8.5 The average depth of Indian Ocean is about 3000 m. Calculate the fractional compression, ∆V/V, of water at the bottom of the ocean, given that the bulk modulus of water is 2.2 × 109 N m–2. (Take g = 10 m s–2)

5.4 Poisson’s Ratio

Simon Poisson pointed out that within the elastic limit, lateral strain is directly proportional to the longitudinal strain. The ratio of the lateral strain to the longitudinal strain in a stretched wire is called Poisson’s Ratio.

👉 The strain perpendicular to the applied force is called lateral strain

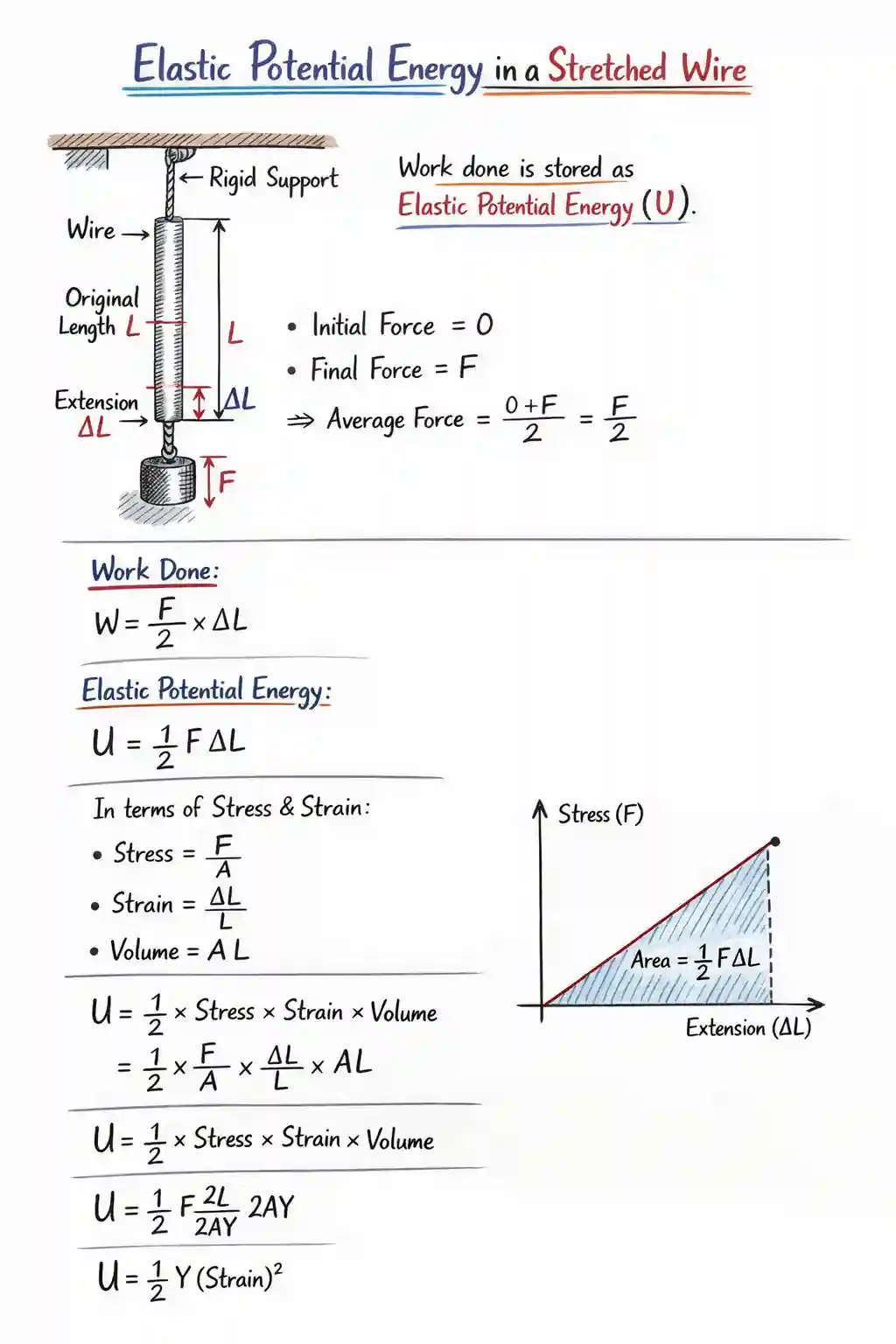

Elastic Potential Energy in a Stretched Wire

When a wire is stretched by applying a force within its elastic limit, work is done against the restoring elastic forces developed in the wire.

This work done is stored in the wire in the form of elastic potential energy.

Applications of Elastic Behaviour of Materials

The elastic behaviour of materials plays an important role in engineering, construction, medicine, and daily life. Some important applications are given below:

1️⃣ Construction of Buildings and Bridges

Materials like steel and concrete are chosen because they have high elastic limits. They can withstand large stresses and regain their original shape when the load is removed, ensuring safety and stability of structures.

2️⃣ Design of Springs

Springs used in vehicle suspensions, weighing machines, and shock absorbers work on the principle of elasticity. They deform under load and return to their original shape when the load is removed.

3️⃣ Railway Tracks and Road Construction

Gaps are left between railway tracks and expansion joints are provided in bridges to allow elastic expansion and contraction due to temperature changes, preventing cracks or bending.

4️⃣ Manufacturing of Wires and Cables

Materials with suitable elastic properties are used for electric wires, suspension cables, and ropes, so that they can bear loads without permanent deformation.

5️⃣ Shock Absorbers in Vehicles

Shock absorbers use elastic materials to absorb sudden jerks and vibrations, providing comfort and preventing damage to the vehicle.

6️⃣ Medical Applications

Elastic materials are used in prosthetic limbs, artificial joints, bandages, and orthodontic braces, where controlled deformation and recovery are essential.

7️⃣ Sports Equipment

Items like bows, rackets, trampolines, and pole vaults rely on elastic behaviour to store and release energy efficiently.

8️⃣ Measuring Instruments

Instruments such as spring balances and pressure gauges depend on the elastic deformation of materials for accurate measurement.

FAQs

Stress is not a vector quantity because, unlike force, it cannot be assigned a unique and fixed direction.

Force acting on a body has a definite direction. For example, the force acting on a particular portion of a body across a given surface always acts in a specific direction.

However, stress is defined as the internal force per unit area acting inside a material. The direction of stress depends on the orientation of the surface chosen inside the body. If the orientation of the internal surface is changed, the direction of the force per unit area (stress) also changes.

Since stress does not have a single well-defined direction independent of the surface, it cannot be treated as a vector quantity. Instead, stress is represented by a second-order tensor.

Hooke’s law states that stress is directly proportional to strain, provided the material is within its elastic limit.

In the initial portion of the stress–strain curve, the graph between stress and strain is a straight line passing through the origin. This linear nature shows that:

Hence, Hooke’s law is valid in this region.

Beyond this linear part, the curve becomes non-linear, which means stress is no longer proportional to strain. In this region, permanent deformation may start, and Hooke’s law fails.

In daily life, we often think that a material which stretches more under a given load is more elastic. However, this belief is a misnomer in physics.

In physics, elasticity is defined as the ability of a material to resist deformation and to regain its original shape and size after the deforming force is removed.

For a given load:

- A material that stretches less undergoes smaller strain.

- Smaller strain for the same stress means greater elastic modulus (Young’s modulus).

Mathematically,

For the same stress, a smaller strain gives a larger value of Young’s modulus. A larger Young’s modulus indicates that the material is more elastic.

Hence, a material that stretches less for a given load is considered more elastic, while a material that stretches more (like rubber) is actually less elastic in the scientific sense.

In general, when a deforming force acts on a body in one direction, it can produce strains in other directions as well.

For example, when a wire is stretched by applying a longitudinal force, it undergoes longitudinal strain (increase in length). At the same time, the lateral dimensions (such as the radius or diameter of the wire) decrease, producing lateral strain.

This shows that:

- A single stress can produce more than one type of strain

- Therefore, the proportionality between stress and strain cannot be described by only one elastic constant

Hence, more than one elastic constant is required to completely describe the elastic behaviour of a material.

📌 Poisson’s Ratio

The relation between lateral strain and longitudinal strain is described by another elastic constant called Poisson’s ratio.